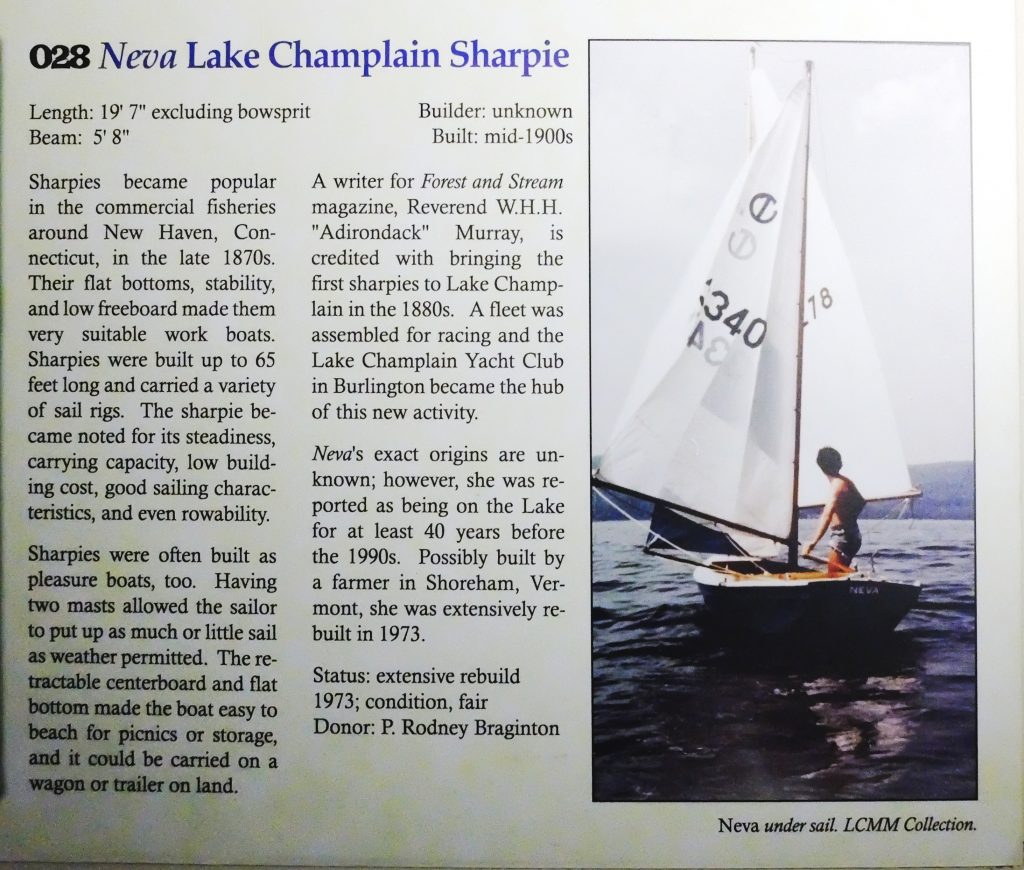

Neva had been lying in a field on the shore of southern Lake Champlain for a couple years when she was given to me in 1972 by the owner who had decided she wasn’t worth saving. She was thought to have been built in the 1890’s at a time when sharpies were popular on the Lake. Howard Chapelle has written extensively about the history and construction of sharpies in American Small Sailing Craft, Boatbuilding, and other books. He describes and shows plans for a sharpie that he measured in 1928 which had been built on Lake Champlain in the 1890’s for racing. The extreme development of these boats as racing machines shows that boatbuilders on the Lake were very familiar with the sharpie type, and makes Neva‘s undocumented lineage believable. Although the main area of sharpie building was centered around New Haven Connecticut, it is possible that the sharpie design originated in Vermont – in American Small Sailing Craft, Chapelle notes that a letter to the editor of Forest and Stream magazine in 1879 claimed that the first sharpie built in New Haven was by a Mr Taylor, a Vermonter. Chapelle’s racing machine was 35′ long and carried a crew of 12, nine of whom used springboards to counterbalance the boat’s heel and keep her on her feet. Neva, by contrast, is 20′ long, modeled more or less on the working sharpies of the Connecticut shore. It is possible that Neva is now the only surviving example of a traditional type once popular on Lake Champlain.

I didn’t know about the history of the boat at the time I got it. The deck was rotted and had to be torn off and rebuilt – in fact, only the side, keelson and bottom planking were in sound condition. The sides are single, width-full, full-length pieces of 1″ clear white pine – lending further credence to her reputed age. That kind of lumber is almost nonexistent today. I wanted a boat for exploring the Lake, and my budget was close to nil. The original rig seemed to have been a large-ish main mast placed at the front of the centerboard case with a small mizzen well aft – I set her up with a more balanced rig, I thought, using second-hand sails from, respectively, a Snipe, a Sailfish and a Turnabout, set on masts cut from some small spruce trees I found here and there. I added the bowsprit for a piratical look and nominally to support the masts; it was not, I’m sure, true to the original rig. Later on, I added an outboard bracket and a 1940’s vintage 5HP Evinrude motor. I used the boat for about six years, keeping it on a mooring in Bridport, Vermont. I was a biology student at UVM for part of that time, and conducted a study of the bivalve clam population of the Lake in the immediate area of my mooring and managed to feel connected with the boat’s ancestry by using it to ‘tong clams’, just like in the old days. I sold her in 1979, the year our son was born, and also the year I acquired my next boat.

That was about 40 years ago. At some point during that time I became aware that Neva had been donated to the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum. The display included photographs of both my wife and my youngest brother, which proof of association I enjoyed.

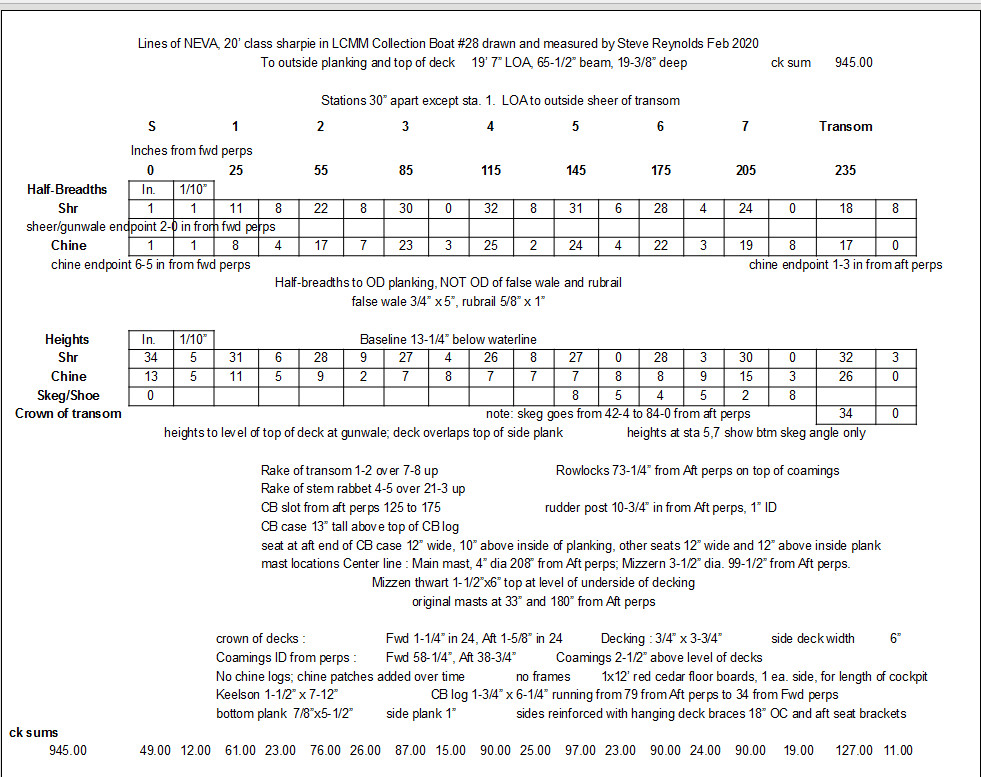

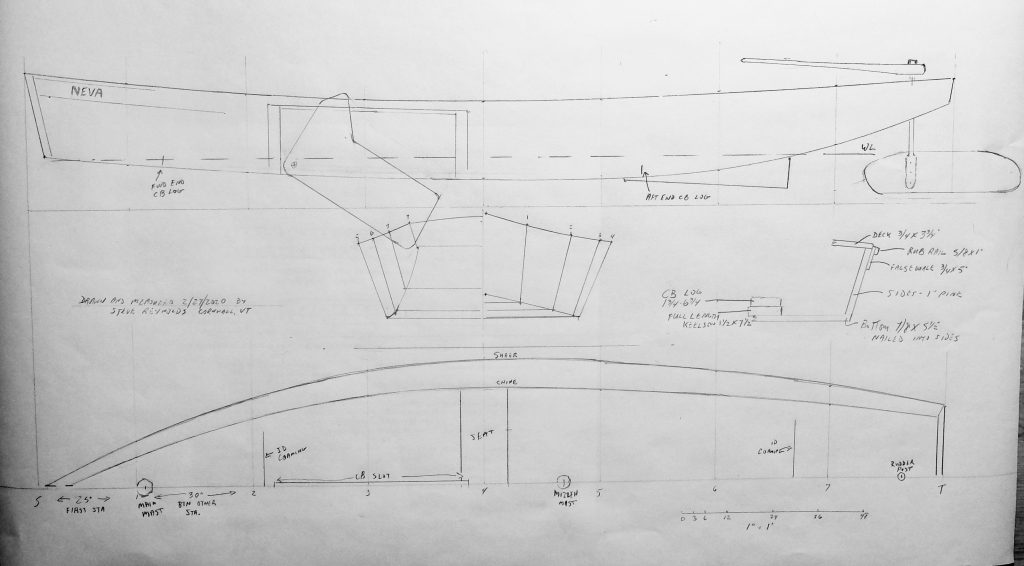

My interest in Neva revived this past winter (2019-2020) when I considered a new building project. My experience with her sailing qualities gave me no particular reason not to build one – the only time I ran into trouble with her, aside from one dismasting in a gust, was running downwind in a breeze and putting her foredeck under a wave as we overtook it. All designs have compromises, etc. etc. I started looking for a table of offsets for a twenty-foot sharpie – and came up with nothing I liked. Chapelle has lines for 24′ boats, which I tried scaling down to 20′, but the result looked exactly as one would expect – it was a scaled down version of a larger boat and the proportions, to function well, can’t all be scaled equally. That is, relatively speaking, the beam can’t be reduced in proportion to the length. I decided to take the lines off Neva and applied to the Museum for permission to do that. I spent a day and a half taking measurements, which I lofted at 40% scale (using the 1″=1cm method) to develop the table of offsets.

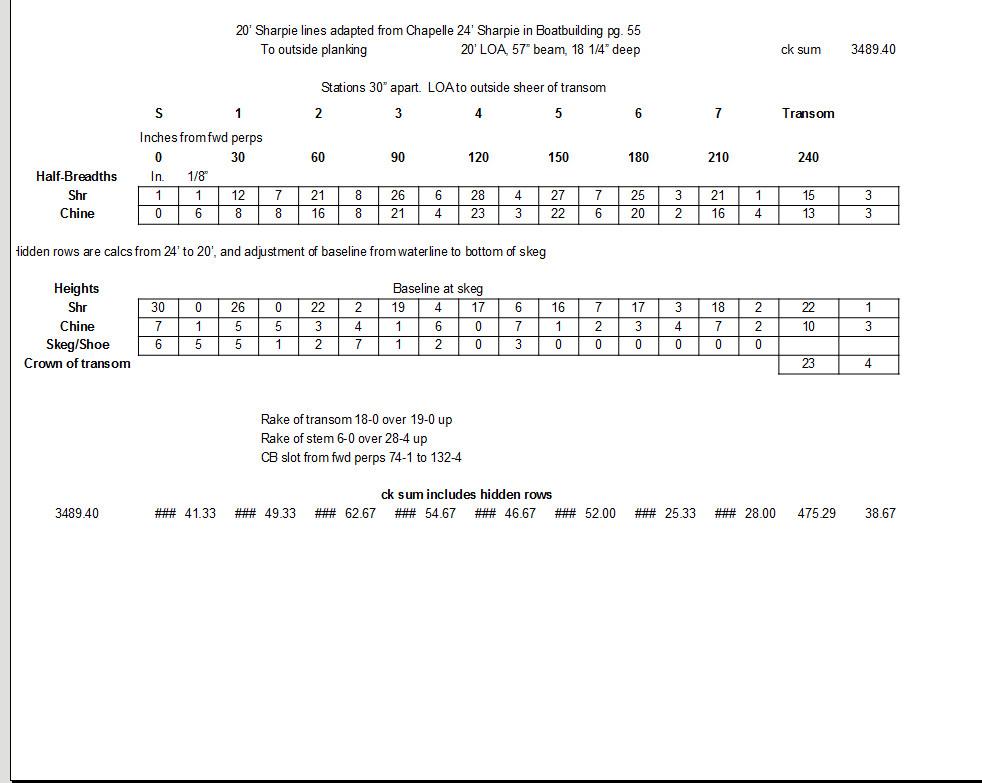

To illustrate my point about not scaling a larger boat down, below are the offsets for Chapelle’s 24′ sharpie, scaled down to 20′. For example, note how the maximum beam of the scaled-down boat is 4″ narrower at the sheer, and 2″ narrower at the chine. It looks pretty, but would not be a satisfactory sailboat.

I will go into some construction details in a future blog.